Beto Shwafaty (born 1977, São Paulo) is a Brazilian conceptual artist, visual researcher and critic working with critical design, spatial politics, knowledge economy, and visual culture. His work is a firm and unapologetic political manifesto against the inequalities of society rooted in his personal experience as well as his archival and historical research. He has exhibited his works widely in institutional contexts while retaining a critical eye towards the silencing mechanisms of the art world. Shwafaty has been involved in collective, research-based, curatorial and spatial practices since the early 2000s and has used methods ranging from installations, sculptural and spatial situations, design and printed matter to research-based and docu-fictional strategies, he explores the possibilities of being simultaneously a productive agent and a reflexive, critical actor.

Àngels Miralda: You practice as an artist, curator, and art critic. How did you get into all of these facets of the art world and how do you balance these roles?

Beto Shwafaty: I have always been curious about many subjects and how they connect in complex – and sometimes invisible – ways to shape our reality. Of course, my background has greatly influenced my practice: after graduating in visual arts in Campinas, Brazil, I worked in the early 2000s as an exhibition coordinator and producer at several institutions in São Paulo and later, with the help of artist Francesco Jodice (with whom I collaborated in his work at the São Paulo Biennial in 2006) I got a scholarship to attend a master’s degree in Milan, at NABA (directed by curator Marco Scotini). This MA was a visual arts and curatorial studies program with a strong political basis, where young curators and artists met side by side. This fact, the breaking down of boundaries between artist and curator, was groundbreaking for me in terms of the freedom to deal with certain disciplines and ideas. After that, I spent a year in Frankfurt, at the Staedelschule, in Simon Starling's class. I believe that these experiences impacted me in such a way that reflection, theory, research and criticism became axes that drive my productive practice and with which I can approach different facets of my interests, which usually fits into a broader idea of how we can articulate the function of art and the artist in an advanced capitalist society like the one we have today.

BS: As for the balance of these activities, there is no clear and planned approach, it is a mix between keeping the practice alive and the opportunities that arise, between creating contacts and responses to what surrounds us. Sometimes, we are lucky enough to find open dialogue and support, other times - or at certain moments - it is a little more difficult to find support as the art world goes through waves and trends that create exclusionary processes so that the value arising from a certain notion of exceptionality can be generated and extracted. It is also important for me to point out here that the notion of "artist etc." (a term coined by the artist Ricardo Basbaum), allowed me to understand and practice these activities as a whole. Thus, in my work, I also end up trying to merge and mix these roles, incorporating the idea of criticism in production, of the text as a place to test aspects of a work of art, of an exhibition and curating as an artistic language to be articulated. We should have the freedom to do so, and also because, in many contexts, precarity and urgency imposes itself on cultural workers in ways that we need to give shape and context to the topics we want to approach with the means at hand. In the end, my practice derives from different moments and contexts, but is informed by a certain core, a certain way of looking at the possibilities and challenges of what I can imagine, and what I want art to be within society.

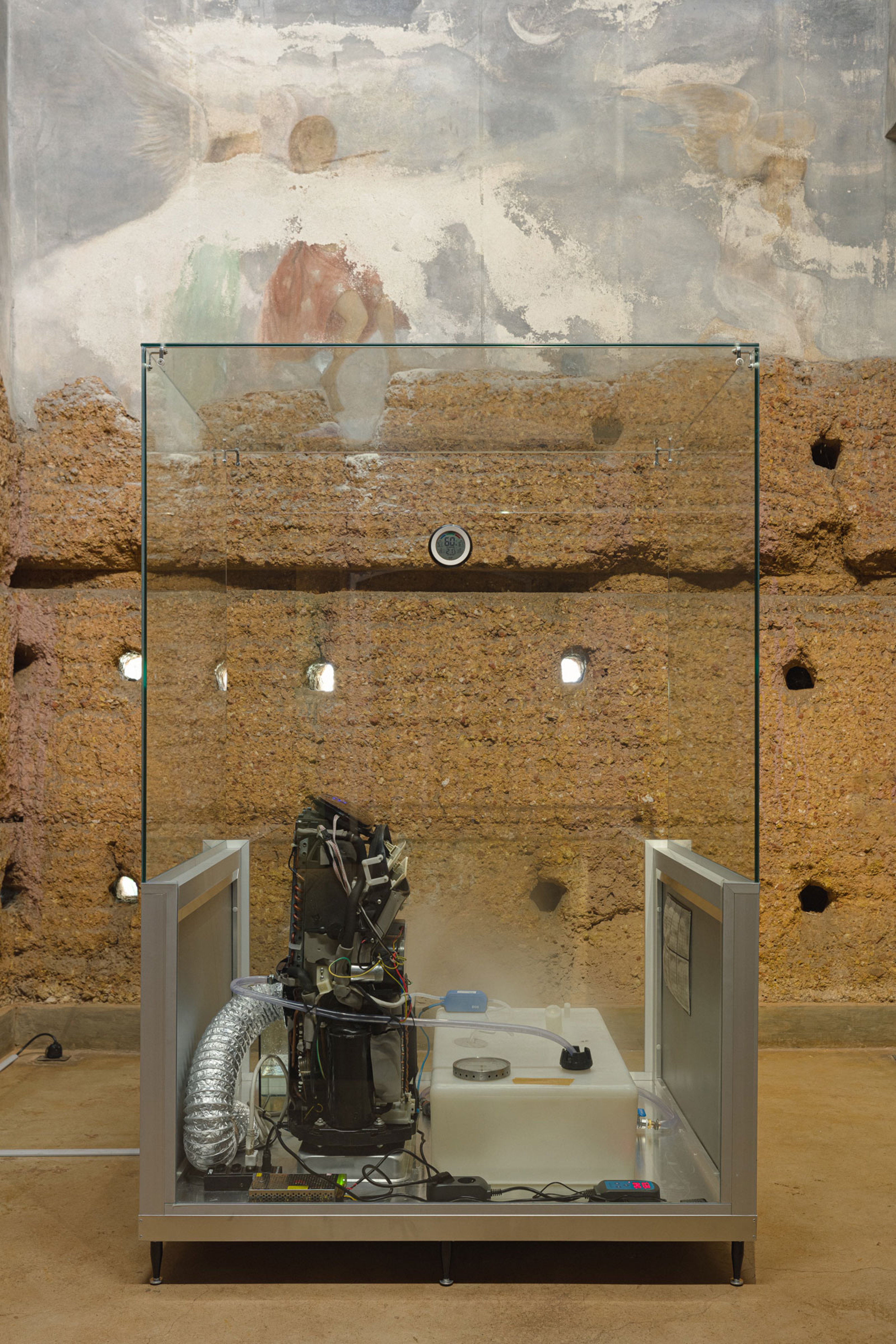

Beto Shwafaty / New air is not always good air @Ana Pigosso

ÀM: I want to ask more specifically about your work Phantom Matrix (Old Structures, New Glories) (2016). This work has kinetic elements such as functioning gears of a seventeenth century sugar cane mill, that points directly to Brazil’s colonial history. You slowly dismantled this archaic device and arranged its elements in a machinic order in an exterior courtyard. Finally, these elements were taken away but left traces imprinted onto the ground. This is a moving performative metaphor of the trudging pace of time and the marks left by industrial violence on space and bodies.

BS: I think it is worth describing the whole project here to give a sense of the entire process. Phantom Matrix (Old Structures, New Glories) was a project developed in 2016 which arose from an invitation by curator and architect Bruno de Almeida. His curatorial project SITU commissioned a series of new site-specific works carried out during his time working with Leme Gallery in São Paulo. The initial drive of the invitation was to seek a critical dialogue with the city, with the urban, with its social, economic and historical fabrics. Since my practice has a strong basis in research, I began an investigation into the urban context of the gallery. It is situated in the Butantã neighborhood, where one of the first sugar cane farms in São Paulo state was placed in the early colonial times. Sugar was a major export of coloniality and was the main commodity of the first plantations in Brazil. Based on this fact, I focused on how to update this economic matrix based on colonial exploitation with the self fulfilling rhetoric about the city of São Paulo, which calls itself the “engine of Brazil” but is a very ugly, harsh, unequal, violent and reactionary place. Despite the energy of the city, which in my opinion arises from the daily emergencies we have to face, we are burdened with a very low quality of life and insufficient public services.

Artwork details: Beto Shwafaty / Phantom Matrix (Old Structures, New Glories), 2016

BS: Afterwards, I set out to try to find this rudimentary machine – the sugarcane mill – and it was a huge undertaking, as there are no more examples of it in the state (or I couldn’t find one easily). A stroke of luck led me to find an example of this proto-machine being sold on a website that sells antiques and second-hand items, Mercado Livre. We then brought the piece from the interior of Minas Gerais, over 700 km away from São Paulo. It was put in operation for a month, but this time by electricity rather than animals or the human force of African slaves. After this period of operation, we dismantled the apparatus and laid out its parts for another month in the gallery courtyard, arranged as if they were evidence of an accident or crime. The pieces were laid out in the sun and rain, and after a certain amount of time, we removed all of them. I already suspected that there might be marks of the elements left on the concrete floor, but the final quality of what was imprinted on the floor surprised us. Many people told me that it reminded them of a kind of shroud (as Brazil is a strongly Catholic country). At this stage of the project, we had these ghost marks imprinted on the floor, and the recorded sound of the mill's previous precarious operation in this context.

The entire project functioned as a material and visual metaphor for the rhetoric and cycles of exploration and progress that shape Brazil and that certainly echo in other contexts. As in other works of mine, my observations started from the past and reflect on what expectations are predicted for the future based on our actions today. We are always in this place, at the present but looking back to try to design what lies ahead that is still invisible.

ÀM: How do you work with the elements of construction and dismantling more broadly in your practice and what is the potential of spaces of memory and grief?

BS: I always operate in ways that unite disparate elements to generate a new reading and understanding of a given issue, or dismantle something known and place it in processes that open up the reflections I intend to point out. Often the idea of migrating forms, translating concepts and shifting contexts also become the axes of operations where I try to address how political and sociocultural issues from society also converge to the art and cultural field. Each project indicates its own logic of operation, its process of existence and I try to listen to the context, to the materiality in place, and to then define the logics of communication and materialization that can be the most challenging and effective. It is a dialogue between ideas and matter that I pursue and gather with the various layers of possibilities that a given context offers. Memory is something that can evoke mourning given the heavy histories that we have in our social formation, but I like to think of the word mourning with other meanings, and in Portuguese mourning also means the verb and the act of fighting – Luto.

Beto Shwafaty / El Museo Impossible de las Cosas Vivas, 2014

ÀM: As an artist from and working in the Global South you face a different set of challenges from artists in the West, what is the potential for Collecteurs to create connections outside of traditional channels and regional connections?

BS: I would like to challenge these terms that have become popular in the art world. I see the Global South everywhere, in the outskirts of Paris, New York, London, as in São Paulo, Lagos, Mexico City and Cape Town we have enclaves of extreme wealth and luxury that are normally associated with the idea of what would be the “Western” ideal. The Global South for me is part of the West, the part that the West would not like to be revealed and that it does not want to recognize as derived from its exploitations. So by giving another name to this phantom part of Western progress, a certain external control is assumed again, because in separating this unwanted phantom, one determines that it can exist and be controlled in a specific, separate place. I would rather not have a name, or try to have many names as the devil itself. This also reminds me of the evangelical TV programs where exorcisms were held on television, and the first act of the priest - “in the name of the flame of God” as they used to scream - was to ask and to know the name of the demoniac entity supposedly in possession of the person.

Recently I have been looking again at the history of art, to Arte Povera, to certain lines of Conceptual-Process Art and even at the already tired waves of Institutional Critique, seeking to look at certain periods in which political precariousness fueled the most radical manifestations as well forms of infiltration and operation. And in this I also have to think about where and what the past movements failed to reach, which I see as a gap we still have: establishing a certain type of general basic infrastructure of protection and regulation in the art system, aimed at producers, at workers, at the relations built within and around art, and not just trying to respond to or generate larger institutional narratives. Because by playing this game like it is today, we reaffirm the privileged characteristics that operate the art system to the detriment of thinking of it as a place of actual rights. Maybe we need a sort of social contract for the art field too.

Having made this unorthodox observation of mine on the subject of the Global South (as I see it), and some precarities of our art system, I believe that initiatives like Collecteurs have the great potential to create important insights, by giving visibility to issues that the mainstream art system perhaps does not value very much. I believe that Collecteurs can be a place for free encounters and frank dialogues, which generate possible alliances in conceptual and practical terms. As a digital platform, it certainly allows for the generation of content and projects, and so it can allow people with consonant desires, imaginations and visions to come together and create new contexts beyond the local level. For this we need to generate the involvement of participating subjects to participate in the production and organization based on collective, democratic, critical and horizontal dynamics.

Beto Shwafaty / Embargo, 2024

Beto Shwafaty / OSPB, 2019

ÀM: Lastly, can you tell us what projects you are currently working on that we can look forward to following in the coming months?

BS: The last few years have not been easy and I spent a long time with great disbelief in art, its function and possibilities in society. Political polarization has taken hold in the art world. This may not happen in an obvious way, but we have intimately felt the weight of capital and the interests of those who hold it, threatening and challenging those who take a stand against current problems, as some stakeholders in the art world end up having involvements of various kinds with this capital or hypocritical ideological positions. Dissent has given way to a certain type of intolerance and the control of resources has made us clearly see how fragile the system in which we operate and do our work is. We naively thought it was a field of freedom, criticism and reflection to try to find a common ground of dialogue, but it is only up to a certain point.

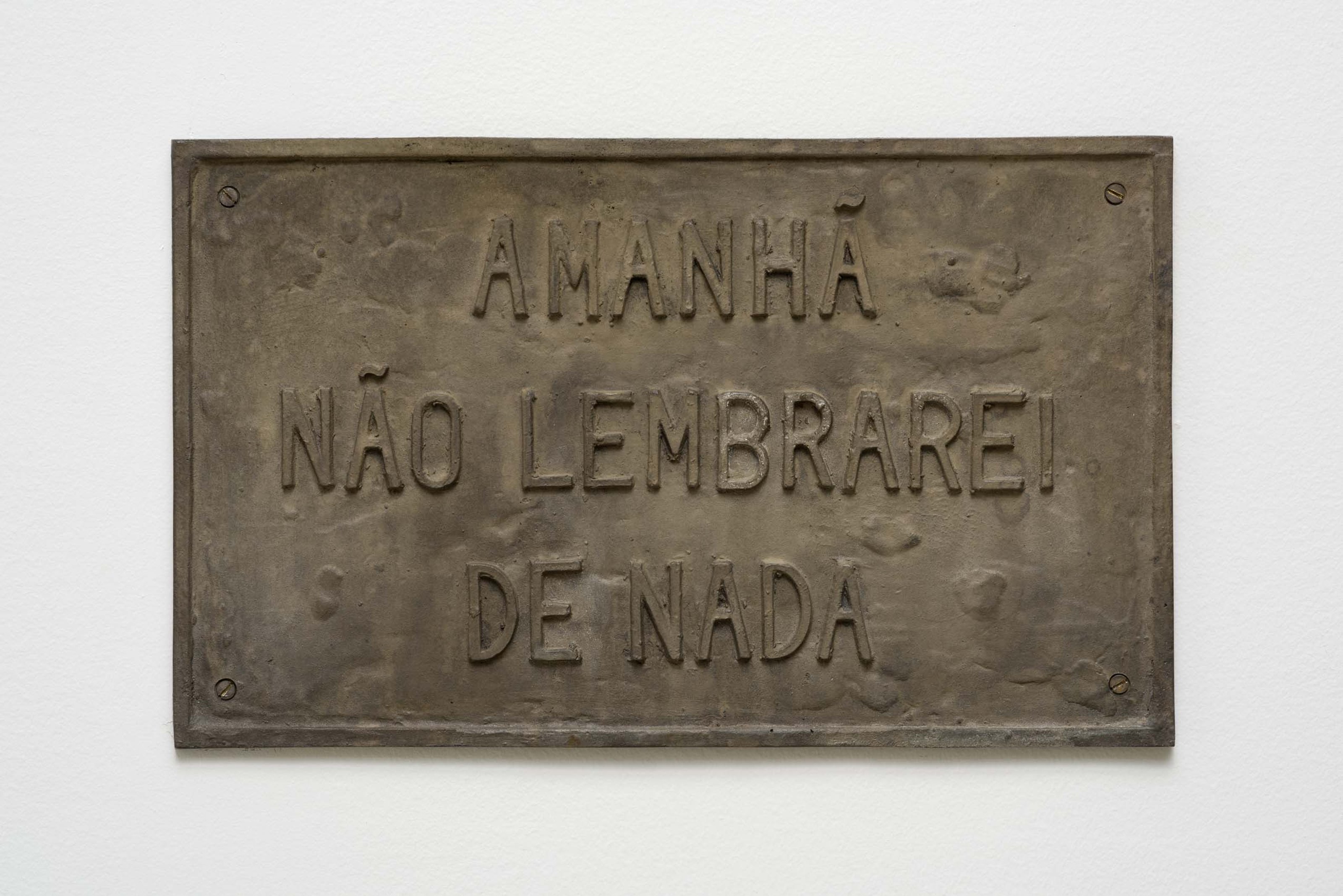

Beto Shwafaty / Tomorrow I will remember nothing, 2019

After these reflections, I am revisiting past projects that were on hold and I am developing new ones, reviewing many strategies and ways of acting and producing and what the real needs of production are. So, in this whole process I have begun to find new contexts and interlocutors, which is very good. I recently participated in a duo show called “Depois do Silencio” with artist Flavio Cury who lives in Germany. This show was curated by Osmar Porto in a new independent art space in São Paulo called Orlando, which is directed by curator Giovanna Bragaglia. I also participated in the Post-Colonia festival in Italy, curated by Martina Angelotti (with whom I have worked in the past) and Emanuele Guidi. This year I will also participate in two institutional exhibitions in museums and cultural centers in Brazil: one that will address environmental, climate and agro ecological issues; and another that will address phenomena of digital networks, fiction, post-truth and memes as a field of conflict for current narratives. In addition to these, I am developing ideas for personal exhibitions and the development of some new works and projects, but they are still in their beginnings.

End.